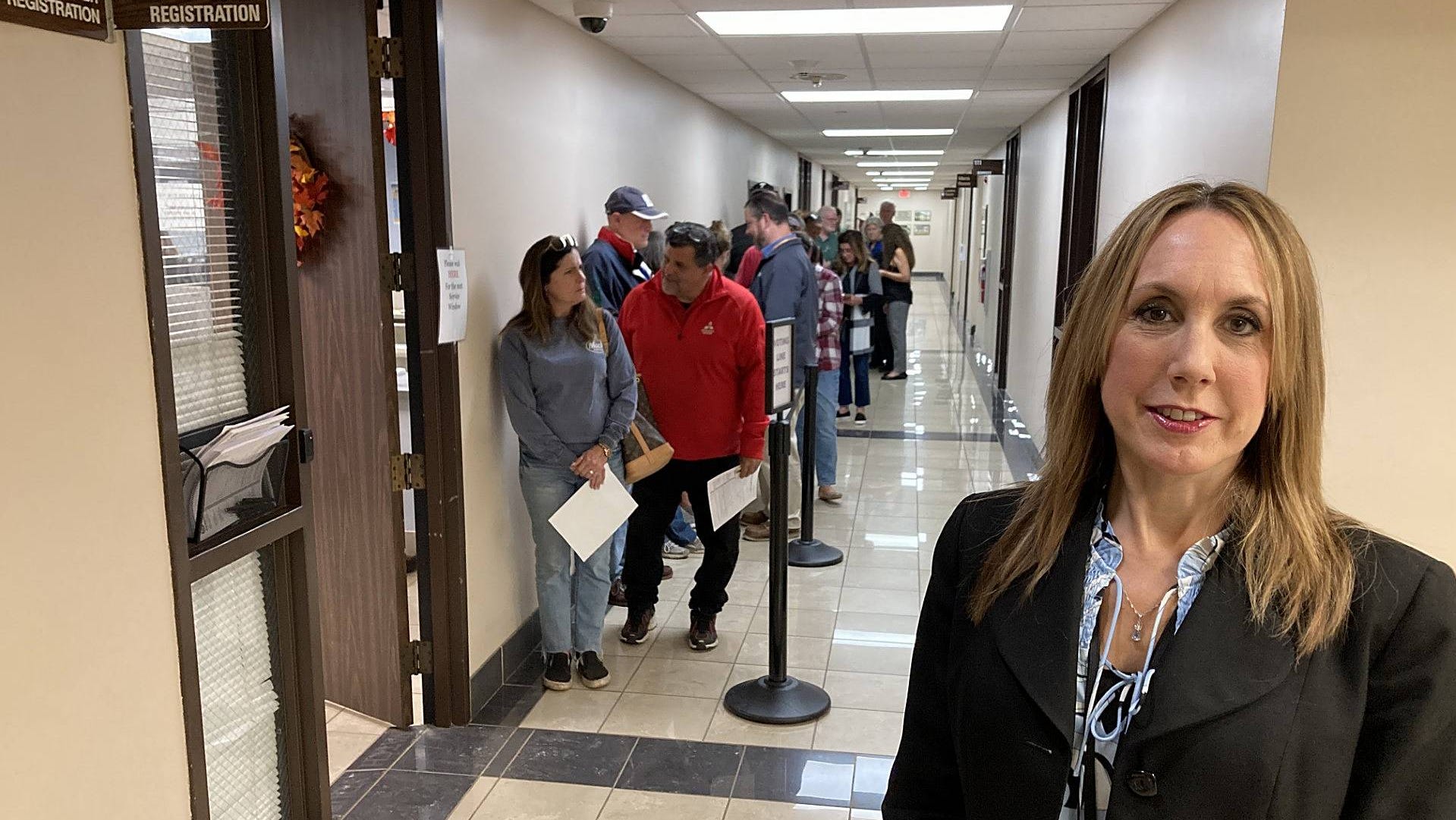

The Erie County Clerk explains the early in-person voting process

Erie County Clerk Karen Chilcott describes the early in-person voting process as people wait to vote Friday at the Erie County Courthouse.

Brian Pietrzak didn’t think there was any problem with his decision to vote absentee ballots in Erie County this year.

He and his wife are living temporarily in Stamford, Conn., where they are trying to start a brewery, but they still have their permanent home in Pennsylvania and plan to return at some point. So Petrzak was surprised earlier this year to open a letter sent by people whose names he did not recognize but who questioned his status as an Erie County voter.

“To help restore confidence in the election, I have volunteered to reach out to people who may have moved to remind them to update or cancel their county registration information,” the statement said.

A copy of the official form that people must fill out to remove their voter registration in Pennsylvania has been attached. The senders also provided a stamped, pre-addressed envelope that he could use to mail the completed form to the Erie County Elections Office.

As far as Erie County Clerk Karen Chillcott is aware, GOP activists have sent similar messages to thousands of Pennsylvania voters in recent months, confusing and even angering some of their recipients.

“People are a little confused because they want to know how did someone get their address? Why is this happening?” Chilcott said.

The letters appear to be part of a broader push by 2020 election detractors to purge voter rolls that they say are cluttered with outdated registration data, opening the door to hackers. These groups used questionable data sources to find these allegedly incorrect records and usually failed to convince the voters to carry out the mass purges they seek.

But an Erie County group took a different tack: asking voters to delete their own records.

“I found it somewhat disturbing”

The letter Petrzak received said U.S. Postal Service records indicated he may have moved from Pennsylvania. In a postscript, the senders wrote that if the recipient still lives in the county, “please ignore” the message.

Petrzak said he wasn’t sure what to make of the message: Was it a form of harassment? Was it bullying? Was it some kind of scam?

“What worries me is that these people that I don’t know … they’re knocking on our door through the USPS and they’re saying we have to cancel voter registration in Pennsylvania,” he said.

Chilcott learned that about a dozen GOP activists have been sending letters to about 4,000 Erie County voters who they believe should be removed from Pennsylvania’s registration rolls. The group appears to be using its own databases to target voters for mailings, but Chilcott is unsure of its source.

Chilcott said she did not know the party affiliation of all the recipients of the letter, but those who expressed concern to her were Democrats.

And she said her office has sent 7,000 notices this year to voters the county has flagged as likely to need to update their registration information. So while she’s not sure exactly what database or technology the activists used, she doubts it’s more accurate given that they notified fewer voters.

“Is it because your system is better or because you only send it to one party?” she wondered.

However, she said she would encourage activists to share their data with the state if they feel they have better sources of information.

Andrew Garber, Voting Rights Program Advisor at Brennan Center for Justicesaid GOP activists across the country routinely compare national change-of-address records, based on mail-forward requests, to voter rolls to target people in mass purges. One problem is that many people redirect their mail during temporary moves, including college students and voters like Petrzak, Garber said.

“The flaws in comparing an old copy of the electoral rolls with the mail-in forms and then assuming that thousands of people need to be removed from the rolls are really obvious,” he said. “Yet it continues over and over again.”

According to Garber, the people behind these efforts typically don’t target voters by party or race, but instead cast “as wide a net as possible” in an effort to make the registration rolls look full of problems.

Ultimately, he said, the goal is to “lay the groundwork for challenging election results that they might not like this fall.”

The State Department advises voters to be vigilant

Brian Schenk, former member of the Erie County Board and Board of Electionssaid he helped the letter-writing campaign by encouraging his followers on social media and podcasts to donate money for the stamps. Michelle Prewitt — an Erie County Republican who has questioned the results of the 2020 presidential election — helped spearhead the effort, with members meeting at parties to stuff envelopes and make labels to prepare mass mailings, he said.

Schenk, who said he was not present at any of the meetings, praised the professionalism Erie County Elections Office but said he believes their regular efforts to clean up local voter rolls are not affecting everyone. GOP activists, whose letter claimed the state had “tens of thousands of inaccurate registrations,” simply stepped in to help, he said.

“They were just trying to make the election as accurate and fair as possible, which would mitigate any potential fraud,” he said.

Previte did not respond to emailed questions.

Petrzak, who used to be a Democrat but is now an independent, checked with the Erie County Elections Office after receiving the letter. They told him he was doing nothing wrong by remaining a Pennsylvania voter, and he has since sent in an absentee ballot.

Pennsylvania Secretary of State Al Schmidt said he would be concerned about the reliability of the information Erie County activists are using to compile their voter rolls.

Election databases assign unique identifiers to each voter so that people with the same name are not confused. But without that safeguard, identity confusion is possible, as he said he learned while helping to investigate hundreds of allegations of voter fraud during his tenure as a top GOP official in Philadelphia.

Officials in his office said they had heard of Pennsylvanians receiving letters similar to the one Petrzak received, warning voters to beware of “opportunistic bad actors” during the election.

“The right to vote is sacred, and the Department condemns any attempt to mislead Pennsylvanians about their voter status,” state department officials said in a statement. “People should not be alarmed, but they should be vigilant if a mailing, email or text message appears to be false or does not come from a trusted source.”

Officials of the Pennsylvania Election Commission regularly clean the voter rolls

Sam Talarico, chairman of the Erie County Democratic Party, said he became aware of the letters a couple of months ago. He calls them form intimidation of voters.

“They’re just trying to create chaos,” he said in a telephone interview.

There is no need, he added, to harass the District Election Commission by removing voters from the rolls.

“Our electoral service, we call them the gold standard,” he said. “They do a fantastic job.”

Pennsylvania election officials routinely use U.S. Postal Service change of address records to identify voters who may have moved, but they are not allowed to cancel registration based on that alone and must first send the person several required notices.

According to the state department, they can remove someone from the rolls if that person does not respond to notices and vote in two more federal elections.

ERIC, a partnership on data exchange between 24 states including Pennsylvania, alerts election officials when a voter is found to be registered in more than one state. Officials then investigate and send notices to those voters to prevent duplication.

Election officials also cancel the registration of people who haven’t voted in more than five years and don’t respond to messages, or if they learn of a person’s death from state or local officials.

Last year, Pennsylvania officials more than 420,000 people were deported from voter lists, the state department told lawmakers.

However, all of these updates must be completed at least 90 days before the election to protect voter lists from massive changes during this so-called quiet period. During this period, offices can only cancel records of voters who have died or require deletion.

US Department of Justice warned at the beginning of this year against systematic updates of voter lists based on “third-party submissions” and said information provided by a third party cannot be considered a deletion requested by the voter himself.

Bethany Rogers is an investigative reporter for USA TODAY Network’s Pennsylvania Capital Bureau.